In their 1993 paper, made famous in Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers, K. Anders Ericsson et al argue that to become an expert at something (think violinist, concert pianist, etc) you must log 10,000 or more hours of practice1. And, they don’t mean just any kind of practice. They refer to “a kind of practice that includes an ‘active search for methods to improve performance,’ immediate informative feedback, structure, supervision from an expert, and ‘close attention to every detail of performance “each one done correctly, time and again, until excellence in every detail becomes firmly ingrained habit”‘”2.

That equates to about ten years if you practice for twenty hours a week every week. In other words, rather than being the product of natural talent, expert proficiency, they argue, is a product of a lot of hard work. Of course, this flies in the face of our culture’s obsession with instant gratification and the quick fix. Want to be an expert at something? Read this book, apply these principles, summon your innate ability and BOOM! you’re there. Contrast this with a prescribed regimen of hard work, and it sounds like you’re taking advice from someone who still lives in a world filled with typewriters and rotary phones.

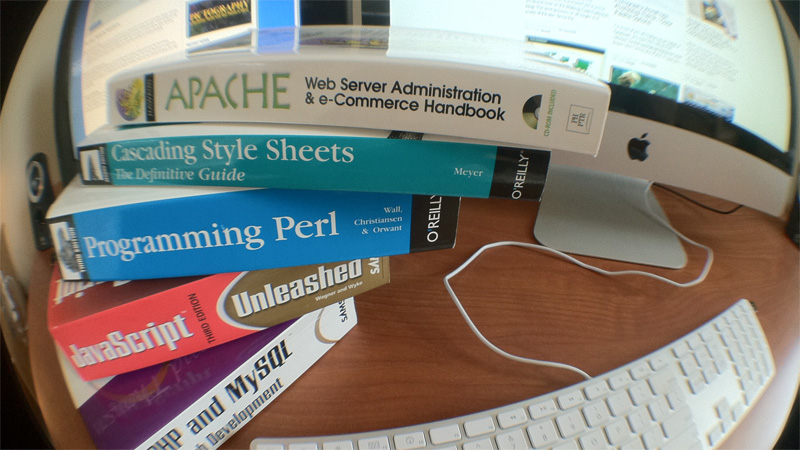

All of these ideas got me thinking about my career as a web developer. September 17th will mark ten years since I took my first project as a freelancer. During that time I’ve built a lot of websites, picked up several new skills and cultivated relationships with clients and colleagues which persist to this day. Although there are better designers and developers out there, in some sense of the word, having spent forty or so hours a week working on the web for ten+ years straight, I feel safe in saying I’m an expert at what I do: I help my clients go from concept to fully hosted website in as efficient and “painless” manner as possible. My business isn’t just about the websites I create, but also the client interaction that goes along with them. My development process as it stands now is the product of years of applied effort and cultivation of my craft. This has become evident to me via two recent interactions: one with a client and the other with a person I’ve been mentoring.

A couple of months ago, one of my clients asked me to train one of their staff who had been promoted to a new position. This new position combined both overall company marketing and branding along with responsibility, oversight and management of the company’s multiple websites.

Upon meeting this person, it was evident that he came from a good design background; however, he lacked any concept of how modern websites work. He was used to designing and building a website’s front-end without having to worry about the backend code, the database, and the site’s interaction with the server. This type of specialization is perfectly acceptable at a bigger company. Having specialists allows for certain efficiencies when teams are working together on projects. You do what you do well, while others do what they do well. However, this new position required that in addition to being a “web designer”, he also be a “web developer”, and my client wanted me to teach him. Without saying this out loud, I questioned whether my client’s request was possible. I can’t teach someone to do what I do over ten to twenty hours of consulting. But, I decided I’d try, and together we’d see what was possible.

As it turned out, my initial concerns held true. Over the course of many emails and a handful of on-site meetings, rather than working his way towards proficiency, this designer was becoming overwhelmed. Part of the problem was his desire to learn, and I don’t blame him. He had so much mental capital invested in marketing and branding for the entire company, that he didn’t have time for learning how to manage all the company’s websites. The more I worked with this person, the more apparent this situation became to me. So much in fact, that I wasn’t a bit surprised to learn later that he’d given them his notice. He’d found another job, and my guess is that it’s one where he can continue to specialize as a designer.

In the other situation I mentioned, I’ve been mentoring a friend by inviting him into my office to shadow me while I work. On and off for the past year and a half, I’ve spent a couple of hours with my protegé every other Friday afternoon. We’ve covered the gamut of what I do. I’ve shown him how I code sites, administer servers and create graphics. We’ve talked theory, trade-craft and business process. He’s been a great student and an avid learner. At times I douse him with a fire-hose of information, other times we focus on one detail. Along the way, things have begun to stick, and he has enjoyed several “Ah-ha!” moments. Given our limited time together, we both realize that this won’t make him an expert web developer, but it has broadened his “digital horizons” and sparked his creativity.

Lately I’ve been wondering, and this gets us to my real reason for writing this post, “What exactly would it take for me to bring my friend up to my level of expertise?” More time and practice would help, but how best to facilitate that? In addition, many of my clients share that it’s the little things, the in-tangibles like good communication and rapport that keep them coming back to use my services. It’s not so much that I’m a good web developer, it’s that my clients see me as a person of good character who handles their online needs. And, if that really is true about me, then training someone else to be all of those things involves more than just sharing information. It requires an apprenticeship.

If I really wanted to train my friend to do all that I do, one of the best ways to do it would be to have him move in and become a part of my family so we could share our lives together. This would require great sacrifice on both of our parts, but the close proximity would maximize the potential for learning and training. I wouldn’t be limited to sharing just technical knowledge. I could also share my lifestyle. I could show how I balance my professional and personal live and help him to do the same.

Now, before my friend or anyone else gets the idea that I’m accepting applications for an apprenticeship, I’ll let you know that I’m not currently up to this challenge. However, all this talk about sharing knowledge and lives has gotten me thinking about you. What is your expertise? What have you spent most of your time doing? Is it related to your career or a hobby? Are you an expert mechanic? Do you have three degrees worth of “life-time experience” raising children? Do you have excellent inter-personal skills honed from a lifetime of studying and getting to know people?

If you pause to think about it, you probably have some level of expertise at something. What is it, and how do you share it with others? Hopefully, I’ve gotten you thinking, and I’d love it if you’d please share your expertise in the comments…

1The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance – By Ericsson, K. Anders; Krampe, Ralf T.; Tesch-Römer, Clemens, Psychological Review, Vol 100(3), Jul 1993, 363-406.

2Composition 1.01: How Email Can Change the Way Professors Teach – James Somers – The Atlantic